You can find this article here or read it below.

If you have not already experienced this, the debugging process of programming can be traumatizing. Relentless as you may be, eventually, when something goes wrong and you seem to have tried everything, you will reach a point that makes you doubt your love for programming. After a while, the excitement of coding will have long been shadowed by the fear of reliving endless debugging. So why does this happen and what can we do about it?

Beyond the obvious benefits associated with increased productivity, this problem needs to be solved because ripping your hair out just doesn't seem to work anymore. The goal of ATS is to restore your love of coding by providing you with interesting functional features combined with a methodology for reducing debugging and testing - and hence increasing your productivity. To understand the benefits of this process, we first need to take a step back and look at the components of the current process.

Bob is assigned a task. Bob decides to start coding pretty much right away. A few hours in, Bob realizes he misunderstood part of the statement of the task and should patch a few things up before continuing. Bob continues coding and eventually reachs a point, out of nowhere, where this terrible feeling comes over him that he ought to test what he's written so far so as to avoid even lengthier debugging later on. Bob then discovers a few bugs and battles with the code in order to pass some unit tests. In this battle the means justify the ends and Bob's code gets cluttered with hacks and other small patches that, accumulated, make his code unmaintainable.

Bob then repeats this process - every iteration more intellectually acrobatic than the previous - until Bob has something workable that somewhat sort of solves a very small subset of the problem. Bob's code has done the job. Bob's client / manager / friend, then says "Hey, why don't we add feature x and change feature y"

Don't be like Bob because at this point, there is really no feasible alternative to just simply starting from scratch. Clearly, this process has a terrible impact on one's own productivity and love for coding. But it also affects the people you work with and the users of your software. Every coder contributing to this code will have to overcome an unnecessarily steep learning curve in order to "add feature x and change feature y". And overall, neither you nor anyone else will ever want to examine or read through your code again. In turn this drastically dampens the user's experience because software evolution is too slow.

Complexity is a programmer's worst enemy, and as our lives start depending more and more on software, what we code should be just as important as how we code it. Obviously, with enough time, we can have the luxury of focusing on quality. But with deadlines and other obstacles, how can we make this happen? One option is to sharpen the tools you use - means making smarter editors - which is an incredible push toward productivity.

However, this does not directly solve the issue - we need to avoid spaghetti, buggy code from the start. We need to apply the same mathematical rigor with which we analyze algorithms to the way we code. Functional programming is a way of reasoning about programs like mathematical expressions, so as to analyze and compose them to propagate this reasoning into larger software.

The goal is to uncover a methodology that allows a coder to spend less time debugging and more time focusing on quality. For this, we need to ask ourselves: "How do I know the code does what it is supposed to do?".

One view is that code passing all tests equates to correctness. From a mathematical and logical perspective, there is no way to cover an infinite set of paths with a finite set of tests, and the more paths you cover, the more time costly this process becomes. So you can't even make a mathematical statement like "in the limit...". Further, if you think of testing as evaluating a mathematical function, there is no guarantee that this function is bijective - most of the time there is no way of identifying the origin of an error from the error itself.

ATS uses types and theorem proving to flush out bugs statically (i.e. without having to run the code). In the context of Machine Learning, runtime tests can be extremely expensive, and in the context of say crypto-currency, relying solely on testing for validation can be extremely risky and most of the time infeasible. Type errors always point back to the origin of the error and force you to examine the logic of your code instead of finding hacks.

Consider that in order for an if statement to pass typechecking, both the then branch and the else branch need to typecheck. However, at runtime, you can only test one branch at a time. ATS uses types to its advantage in that the coverage of types is total while its precision is, in general, limited. So it encourages the programmer to refine (increase the precision of) the types he/she uses. The idea is then to allow type specification to be so precise that passing typechecking equates to correctness.

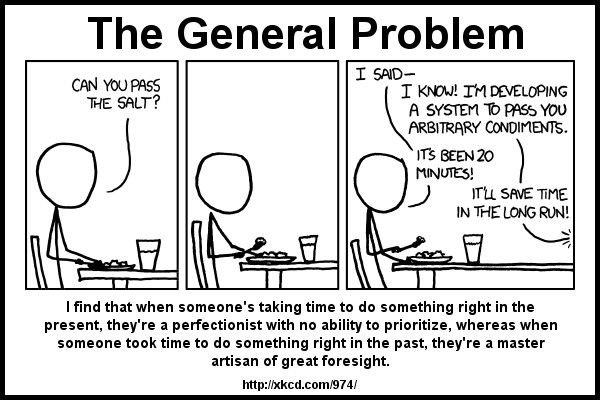

But this kind of precision can negatively affect productivity if used incorrectly. So we need to accompany these language features with a method to use these constructs effectively. The methodology that accompanies each language is truely what distinguishes one language's productivity from another - not how high level or domain specific it is. If, as a coder, your methodology does not change with the language you use, then you will likely be facing the debugger a lot.

The goal of this talk is to outline a methodology and list good practices, that, when combined with ATS, make for an extremely productive workflow. Giving time back to the programmer allows for better focus on quality. It will be up to the reader to decide how to translate this methodology into the constructs of his/her language of choice - here we will focus on ATS

The ATS perspective is to start vague and refine. Start with simple types: the domain of ints maps to the domain of ints via a given function. The typechecker proves that if an int is provided as input then an int is produced as output. Now you can refine the input and output types to match the specification of your function. For example you can define the input to be only ints multiples of 2 and the output to be only ints less than 0. You can statically check whether an index is out of bounds, or whether matrix dimensionality matches for a given multiplication. The refinement is limitless.

There are many excellent tutorials about getting started with ATS and its syntax. The goal of the following (albeit somewhat pendantic) example is simply to illustrate the concept mentioned above - not necessarily to re-iterate the ATS tutorial. Let's start with the factorial function.

Deciding what the input and output types of a function will be is a bit like writing the introduction of an essay: you should write it after you have determined the overall logic and structure of the body. Here, the factorial function we want to implement takes as input a positive integer n and outputs the product of all strictly positive integers less than or equal to n. As such, we can declare our function fact as:

extern

fun

fact(n : int) : intAnd, we can implement it as such:

implement

fact(n) =

if n = 0 then 1

else n * fact(n - 1)This factorial function works for positive integers. However, when n < 0 our factorial function will keep decreasing n without ever hitting the base case. This will give a stack overflow because of the recursion. A naive fix for this solution is the following:

implement

fact(n) =

if n <= 0 then 1

else n * fact(n - 1)This is incorrect because our factorial function should be undefined for values of n < 0. Outputting a default value as such is a hack and should be avoided as much as possible. When you test, later on, how your factorial function integrates with the rest of your code, if the overall output is a blue square instead of an orange circle, there is no way for you to know the cause was a negative value given to fact along the way. We want our program to stop the moment a negative value is given as input to fact. We can do the following:

implement

fact(n) = let

val () = assertloc(n >= 0)

in

if n = 0 then 1

else n * fact(n - 1)

endThe ats assertloc() function will raise an error if the statement ats n >= 0 is false. At this point we have a working factorial function and we can start the refinement process. Please check out the following links before proceeding:

Now, we're getting somewhere

Please read the following implementation of the factorial function combining both dependent types and tail-recursion.

In general, especially when coding large projects, a top down approach is extremely productive in ATS.

First, write the code for the function you need to implement. Do not disturb your workflow by implementing the helper functions on the fly. Once you have finished writing your function and you are convinced the logic of your program is sound, simply declare the helper functions. At this point, typecheck your code, read the type errors closely, fix them, and typecheck again. Now that your code passes typechecking, use that same top down approach to tackle the helper functions that are declared but not implemented.

The reason this method is effective is because a trip to the debugger, print statements in your code, unit tests, all require more time than simply typechecking. They all break your workflow and require you to have runnable code at every stage. This forces you to adopt a bottom up approach with no guarantees that the code you write will be needed later on.

Once you have all the code written you can delay tests even further by refining the types and constructing proofs that help flush out potential bugs.

It is important to distinguish the imprecise from the flexible. In some languages, functions are overloaded until they become imprecise - it becomes extremely difficult to predict what the output will be for a given input. Think about applying the length function in Python to a 2D array. You can guess that the function will return the number of rows if you store your matrix in row major. But what if now you have a 3D array or an ND array. You can easily see that one dimension will be returned, the question is which one? This is because the length function has become imprecise.

On the other hand, some languages require you to be so precise about types and functions that it seems impossible to write code that can be reused in a different context. Technically you could be required to create a new length function for every different object you encounter. Thus repeating a lot of code and being unproductive. So how can we consolidate precision and flexibility?

The solution is polymorphic functions and higher-order functions. They allow for extensive code reuse while preserving precision. They also provide a great foundation for mathematical/ formal reasoning about your program.

ATS has a large combinator library that can make your code elegant and readable. Some of these combinators include

Please take the time to get familiar with these functions before moving along. We will use these combinators to solve Project Euler's problem 18.

A Brute Force algorithm for this will be to explore all possible paths and find the maximum. However, as indicated in the problem statement, we can do better. After a short review of dynamic programming, we notice we can fold the triangle onto itself in such a way to obtain a list of the max paths to each leaf node of the triangle. Then we need only find the maximum of that list. To illustrate this, let us take the smaller triangle from the problem's example:

3

7 4

2 4 6

8 5 9 3

The folding process will gives the following intermediate folded triangles:

first, we add 3 to 7 and 3 to 4.

10 7

2 4 6

8 5 9 3

then we add 10 to 2 and 7 to 6. For 4, we can get to it from 10 and 7 so the max path to 4 will be max(10 + 4, 7 + 4) as such:

12 14 13

8 5 9 3

and finally we get the following list:

20 19 23 16

Each of these number represents the max path to that node. So now that the triangle is fully folded, we simply take the max of the resulting list to get the overall max path. In this case it's 23. Now that we are logically convinced of our methodology, let's write some code!

As before we need to think about how we will define our function. Here we want a function that takes in a triangle tr and returns an integer that represents the max path. As you may have guessed from the combinators above, we will represent a triangle as a list of lists. Our max_path function will have the following declaration:

typedef layer = list0(int)

typedef triangle = list0(layer)

extern

fun

max_path(tr: triangle): intThe typedef above simply gives a name to a type. Here, we define a type called triangle which we choose for now to be a list of layers where a layer is a list of ints (so a triangle is a list of lists of ints). We can implement max_path in the following way:

implement

max_path(tr) =

max

(

list0_foldleft<layer>(tr, nil0(), lam(res, line) => myfold(line, res))

)Now, in order to typecheck this function we need to declare our helper functions:

extern

fun

myfold(xs: layer, ys: layer): layer

extern

fun

max(xs: layer): int Now that our function typechecks, we can implement our helper functions myfold() and max() as such:

implement

myfold(xs, ys) = let

val f1 = list0_map2<int,int><int>(cons0(0, ys), xs, lam(y, x) => x + y)

val f2 = list0_map2<int,int><int>(list0_append(ys, list0_sing(0)), xs, lam(y, x) => x + y)

in

list0_map2<int, int><int>(f1, f2, lam(x, y) => if x > y then x else y)

end

implement

max(xs) = let

val () = assertloc(list0_length(xs) > 0)

fun aux(xs: list0(int), m:int): int =

case+ xs of

| nil0() => m

| cons0(x, xs) => if x > m then aux(xs, x) else aux(xs, m)

in

case- xs of

| cons0(x, xs) => aux(xs, x)

endGreat! After typechecking, we can be fairly confident that this code does what we want it to do. If you would like to play with the code and/or test it out, you can do so online here.

Here you will find a walk through of the MergeSort algorithm implemented in the top down style.

" The manner in which abstract types are supported in ATS is particularly designed

under the guideline to maximally promote refinement-based programming. As I see it,

the ability to make effective use of abstraction in controlling programming complexity

is the most important characteristic of a top programmer, and the type system of ATS

can greatly help one acquire this ability. "

Here is an outline of the code templates I use to structure my ATS code.

The goal is to generate "boring" code. The idea is if your code is boring, it is straightforward and consistent - two crucial premises to readable and maintainable code. Following a template and a style you can conform to makes it easier to write "boring" code.

Lots of functions with small bodies is far more readable than less functions with large bodies

ATS needs space - accross files and folders.

Stay vague until you need to be precise! Please see the following example where the GameLoop function is extremely general.

For more information about ATS, please read the book Introduction to Programming in ATS