- Distinguish categories of differential equation solvers

- Write the strong and weak forms of governing equations in the scramjet system

MIRGE-Com has “higher” goals specifiable only in human language—the simulation of scramjets—but in its internals, it is a differential equation solver, one more in a long and illustrious line.

We will use the Navier-Stokes equation for

In three dimensions, the conserved quantity

The solution of ordinary differential equations is the most fundamental tool: numerical methods for partial differential equations are typically rooted in understanding ODE techniques well. Furthermore, of the three types of ODEs (initial value problems, boundary value problems, and eigenvalue problems), IVPs form the basis for understanding other methods.

Our archetypal IVP for this tutorial is a relationship between the change in a quantity in time and some expression of

f(y, t) $$

Moin: “The aim of all numerical methods for solution of this differential equation is to obtain the solution at time

A direct method approximates the derivatives such as

We typically end up with a system of coupled differential equations when we have either multiple derivatives or multiple points in the grid present. (Which is almost always the case.)

\begin{pmatrix} f_1 \left (x,\mathbf{y},\mathbf{y}',\mathbf{y}'',\ldots, \mathbf{y}^{(n-1)} \right ) \ f_2 \left (x,\mathbf{y},\mathbf{y}',\mathbf{y}'',\ldots, \mathbf{y}^{(n-1)} \right ) \ \vdots \ f_m \left (x,\mathbf{y},\mathbf{y}',\mathbf{y}'',\ldots, \mathbf{y}^{(n-1)} \right) \end{pmatrix} $$

We have three basic families of solution approaches available:

- Explicit matrix solution

- Implicit matrix solution

- Direct stepping methods

If the system of coupled differential equations can be written separately for each time step, and a few mathematical desiderata are satisfied, then the system of equations can be written as a matrix. Formally,

formal $$ \underline{\underline{A}} \vec{y} = \vec{f} $$

where

The particular form of

rearranged as

$$ \left( \frac{1}{h^2} + {a_j}{2h} \right) y_{j+1} + \left( b_j - \frac{2}{h^2} \right) y_{j} + \left( \frac{1}{h^2} - \frac{a_j}{2h} \right) y_{j-1} +

f_j $$

the resulting matrix becomes

\begin{pmatrix} \left( b_1 - \frac{2}{h^2} \right) & \left( \frac{1}{h^2} + {a_1}{2h} \right) & 0 & \hdots \ \left( \frac{1}{h^2} - \frac{a_2}{2h} \right) & \left( b_2 - \frac{2}{h^2} \right) & \left( \frac{1}{h^2} + {a_2}{2h} \right) & \hdots \ 0 & \left( \frac{1}{h^2} - \frac{a_3}{2h} \right) & \left( b_3 - \frac{2}{h^2} \right) & \hdots \ \vdots & & \ddots & \ \end{pmatrix} $$

Note the structure of this matrix. What features do you observe?

Because finite difference schemes are local, depending only on grid-adjacent mesh points, explicit matrices tend to be diagonal and sparse. (This requires constructing the right grid in the first place, too.)

Sparse matrices contain mainly zeroes, and only the occupied points are stored in memory for efficiency.

So why don't we solve all matrices explicitly? Math.

Representation

Formally, given the matrix equation

the solution should be obtained as

\underline{\underline{A}}^{-1} \vec{b} \rightarrow \vec{y} \rightarrow \underline{\underline{I}} \vec{y}

\underline{\underline{A}}^{-1} \vec{f} $$

This is correct, but is quite often computationally inefficient to achieve. For instance, the matrix

Enter LU and QR factorization. A number of ways of algebraically modifying both sides of the equation have been devised.

Existence

Given a matrix equation, does it have a solution? It's not guaranteed to. The numerical methods that we prefer, such as finite difference schemes, have been chosen to yield matrices that are not singular (meaning that there is no inverse matrix).

Stiffness

The differential equations themselves may be stiff, meaning that they resolve on different scales in the independent variables. That is, the solution being sought may vary slowly while adjacent solutions vary quickly.

Conditioning

Another computational challenge relates to the representation of the problem as a matrix as well. The matrix condition number refers to how well-conditioned (or ill-conditioned) a problem formulation is to be solved:

The condition number associated with [a] linear equation gives a bound on how inaccurate the solution x will be after approximation. (Note that this is before the effects of round-off error are taken into account; conditioning is a property of the matrix, not the algorithm or floating-point accuracy of the computer used to solve the corresponding system.) In particular, one should think of the condition number as being (very roughly) the rate at which the solution

$y$ will change with respect to a change in$b$ . Thus, if the condition number is large, even a small error in$b$ may cause a large error in$y$ . On the other hand, if the condition number is small, then the error in$y$ will not be much bigger than the error in$b$ . ¶The condition number is defined more precisely to be the maximum ratio of the relative error in$y$ to the relative error in$b$ .

Finally, not all DE solution methods can be written in a matrix form, or there may be other reasons to avoid an explicit solution, such as efficiency gains in working with already-solved (same-time-step) answers.

If we are not interested or able to solve the explicit matrix formulation, we may adopt an implicit iterative approach. In this case, we look for an approximate solution at a particular accuracy. Typically, we take a candidate solution, re-evaluate the outcome, check for the change (as error), and iterate on this process until the global error is small enough. We anticipate that increasing the number of iterations will sooner or later solve the problem (converging solution).

We can impose a number of requirements on

We define error as

and convergence as

\vec{0} \text{.} $$

(Look up spectral radius for more on this topic.)

MIRGE-Com currently solves by explicitly time-stepping forward, which is basically a piecemeal explicit solution. Steady-state flow would be detected similar to how iterative convergence for an implicit method was just described, except that

A simple approximation to the IVP may be had by selecting a finite difference (rather than an infinitesimal) and then rearranging the result for an explicit statement for the next value.

f(y, t) \approx \frac{y_{n+1} - y_{n}}{\Delta t} $$

∴

This approximation is only stable for extremely small

where

(There are many other solvers. RK4 is the workhorse of time-stepping solvers but it is not suitable for stiff equations.)

leap provides a library of implicit and explicit time-stepping methods in this vein.

- Examine

steppers.py:advance_state. - Examine

integrators.py:rk4_step.

Now that you've seen a lot more of the numerical machinery underlying MIRGE-Com, let's revisit the physical expressions introduced in the first tutorial and find a suitable discretization in space as well as in time.

We begin with the strong form

x + 1 $$

with

By integrating the equations over a volume (thus, a control volume or element), we write the conservation law over the volume rather than over each point. We refer to this formulation as the weak form

\int _{x=0}^{1} dx, (x+1) w(x) $$

Integrate by parts to obtain a statement

- \int _{x=0}^{1} dx, \frac{dy}{dx} \frac{dw}{dx} $$

Strong form and weak form are isomorphic.

The discretized form or Galerkin form

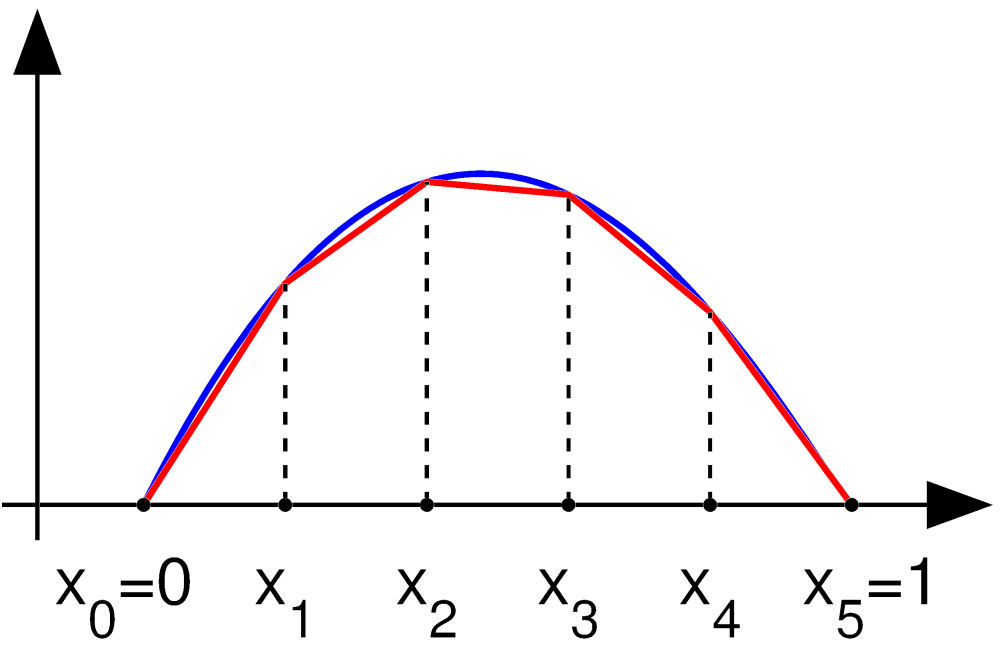

Divide the domain into

for

Besides linear tent functions, one may use Chebyshev polynomials, Lagrange polynomials, Legendre polynomials, all manner of splines, and so forth.

(In many cases, this resulting

In two or three dimensions, the volume is spanned by polynomials in each independent spatial variable.

- Suresh, “Strong, Weak and Finite Element Formulations of 1-D Scalar Problems (ME 964)”

- “Finite Element Method”

grudge discretizes and solves the discontinuous Galerkin operators in space. From MIRGE-Com's perspective, this is a basically invisible process, and decisions about how to best handle a given formulation are left up to grudge. grudge uses pymbolic to handle quantities in the grid.

The general solution process in MIRGE-Com utilizes both time-stepping with RK4 and space-resolved solution with grudge's finite element formulation.